Today’s guest post by Hideaway reviews our ‘plan’ to transition off fossil energy, and shows it is in fact a mirage.

Hideaway is a new force active at un-Denial and other sites that discuss energy and overshoot. He focusses on the feasibility of transitioning our energy system, and brings a data-backed, reality-based, adult conversation into a space that is more often than not filled with ignorance, hope, and denial.

As I was writing a post about EROEI, I came across data for energy production and consumption from Our World in Data. It’s all very professionally made and ‘free’ for anyone to use in their energy discussions.

I spotted one problem though, the data presented has a caveat, they use the substitution method for non-fossil fuel generated electricity, and in the fine print this is explained as… “ Substituted primary energy, which converts non-fossil electricity into their ‘input equivalents’: The amount of primary energy that would be needed if they had the same inefficiencies as fossil fuels. This ‘substitution method’ is adopted by the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy, when all data is compared in exajoules.”

OK, how do they convert non-fossil energy into fossil fuel equivalents??

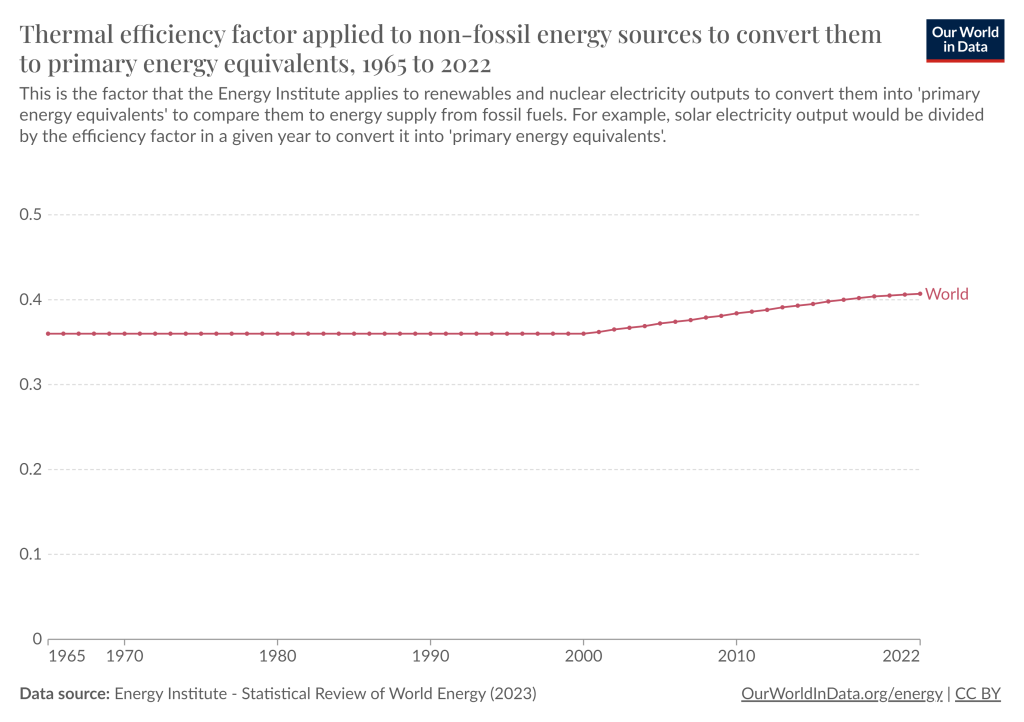

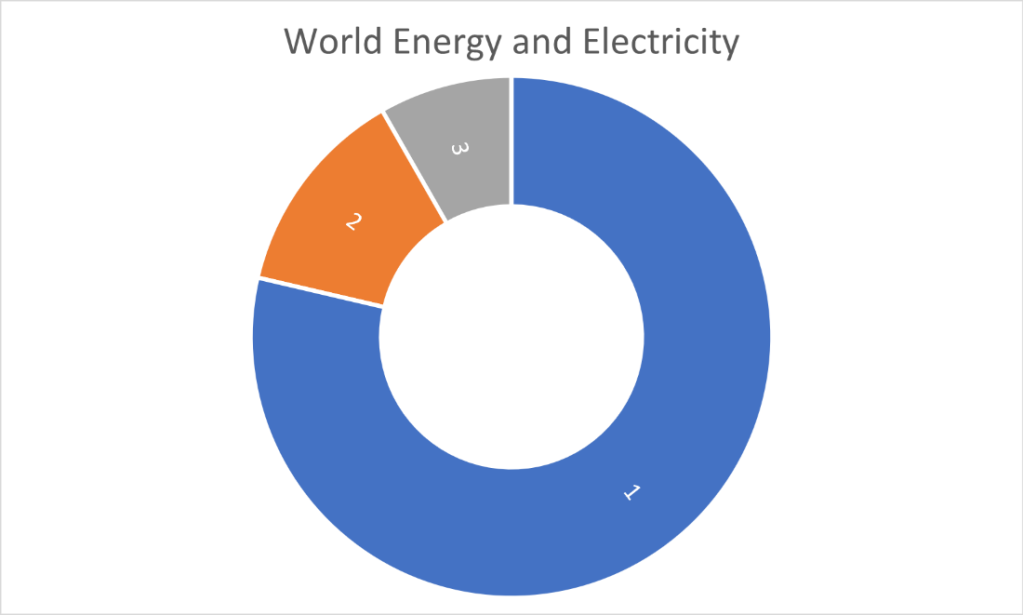

This chart provides the conversion factor.

An efficiency factor of 0.4 means that nuclear, hydro, solar, wind, biofuels and other renewables are made to look much larger than they really are by a factor of 2.5 in the following chart.

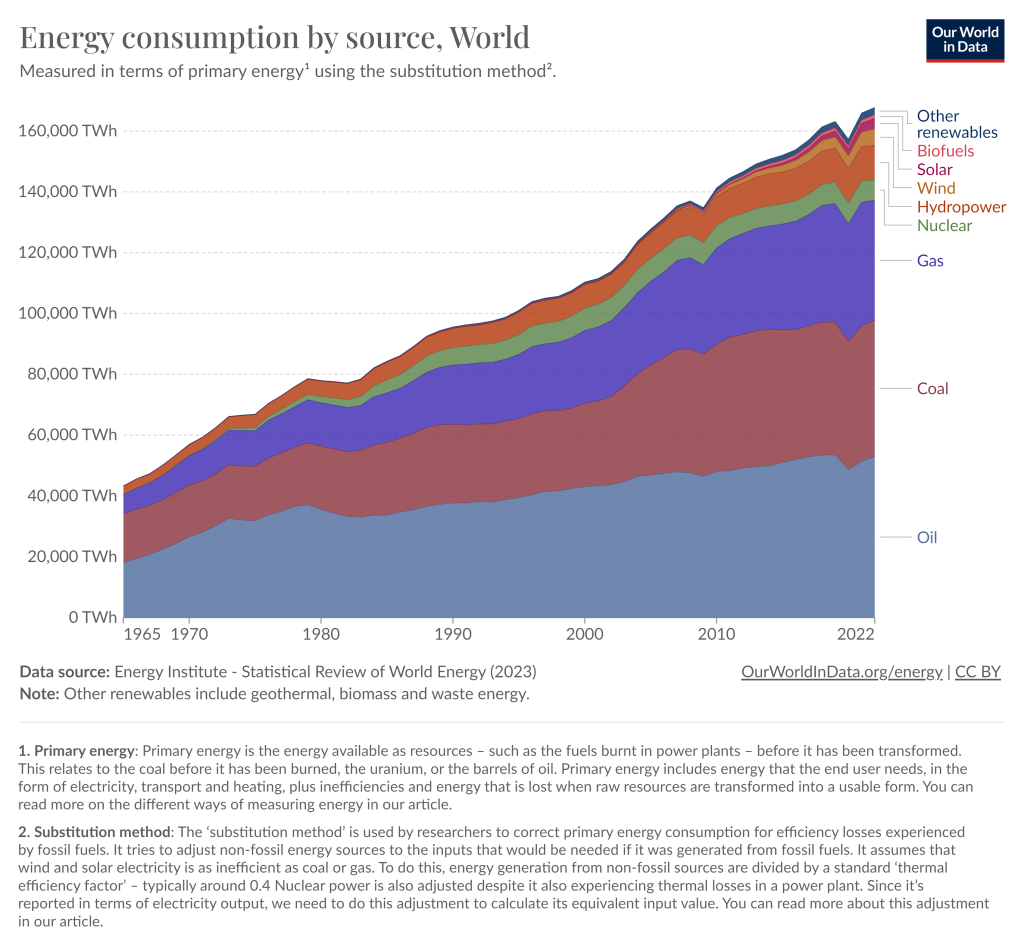

It suggests we are making good progress at replacing fossil with renewable energy, and that with a bit more effort we can convert all fossil energy to renewable electricity.

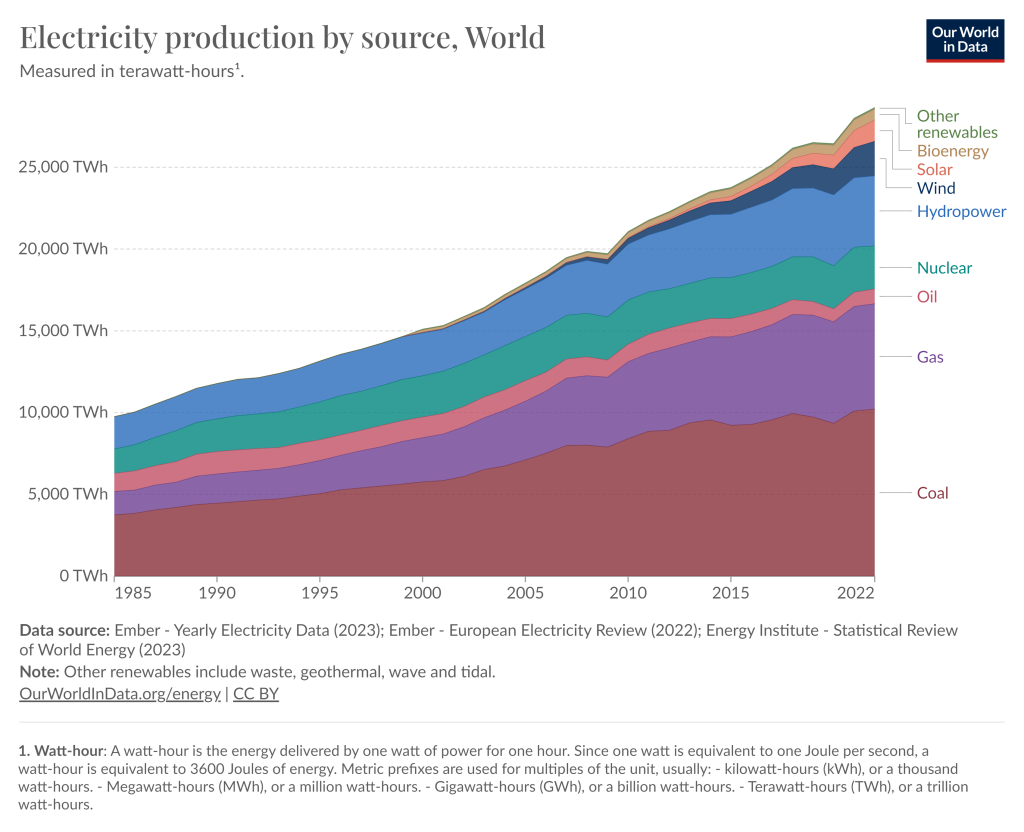

As is common in energy discussions today, reality differs from what is presented. The following chart shows electricity production by source.

Notice that total world electricity consumption for 2022, which of course must equal production, is 28,660Twh. Yet the above chart for energy consumption by source shows that nuclear, hydro, solar, wind and other renewables are by themselves 11,100Twh.

If we divide non-fossil electricity consumed by the 2.5 efficiency factor we get 11,740Twh which is close to the correct amount of non-fossil electricity produced. I say close because the energy from non-fossil sources adds up to 641Twh more than that shown on the electricity production chart, so this extra energy must be used for some other purpose, but has still been treated as 2.5 times more efficient.

From the above chart we see 10,212Twh of electricity from coal and 6,443Twh of electricity from gas, and we can calculate how much of the total oil and gas production was used for electricity by multiplying by 2.5.

From the 44,854Twh of total world coal consumption we used 25,525Twh for electricity, and 19,329Twh for other purposes. Likewise for the 39,412Twh of total world gas consumption we used 16,107Twh for electricity and 23,305Twh for other purposes.

With oil we only produced 904Twh of electricity. Assuming the same 40% efficiency for oil as coal and gas, then only 2,260Twh of oil was used for electricty and 50,710Twh was used for other purposes.

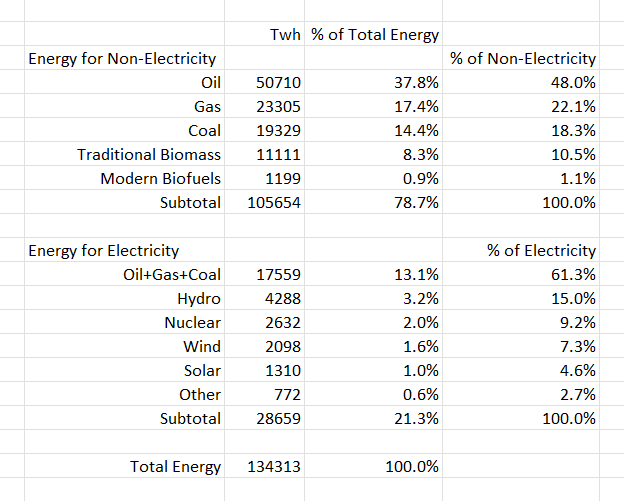

We can now complete the following table and use it for assessing how our energy transition is going.

Total primary energy production is 134,313Twh of which wind and solar contribute 3,408Twh or 2.5%.

Electricity is 21.3% of total energy, and fossil fuels produces 61.3% of electricity.

Only 8.2% of total energy comes from nuclear, hydro, solar, wind, and other renewables, and the remaining 91.8% comes from fossil fuels and traditional biomass.

The following chart illustrates this graphically. Blue is all non-electricity energy, orange is electricity from fossil fuels, and grey is electricity from all other sources.

The world is currently trying to replace fossil fuel produced electricity (orange) with electricity from nuclear, hydro, solar, wind and other ‘sustainable’ methods (grey). It is not possible to manufacture, install, or maintain more ‘sustainable’ energy (grey) without fossil fuels. Even the newest mines and factories require fossil fuels in many forms.

There is no plan for the non-electricity portion of energy (blue).

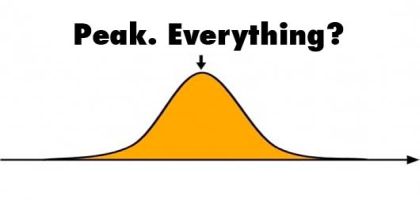

Let’s now consider how fossil fuel and traditional biomass use has changed over time. Are we getting anywhere?

Traditional Biomass was 100% of energy used, according to Our World in Data (OWiD), until coal started to be used in the year 1800 at 1.7% of total energy. Interestingly, they attribute no energy to water power, wind (sails), or animals, perhaps because they were too small or hard to measure.

Fossil Fuels (FF) and Traditional Biomass (TB) contributed 100% of total energy until 1920 when Hydro contributed 1%.

The contribution of FF and TB to total energy changed as follows:

- <1920 100%

- 1920 99%

- 1940 99.2%

- 1960 98.4%

- 1980 97.6%

- 1990 95.2%

- 2000 94.4%

- 2010 94.3%

- 2020 92.1%

- 2022 91.8%

Most energy analyses lump TB in the mix without paying much attention to the size of its contribution. At 11,111Twh, as measured by OWiD, TB is a larger source of energy than nuclear, hydro, wind, solar and biofuels combined! TB is not going to be replaced by any other type of energy. Most energy analyses place TB on the other side of the ledger from FF, when in fact TB should be added to the FF side, as it is burnt and adds to greenhouse gasses.

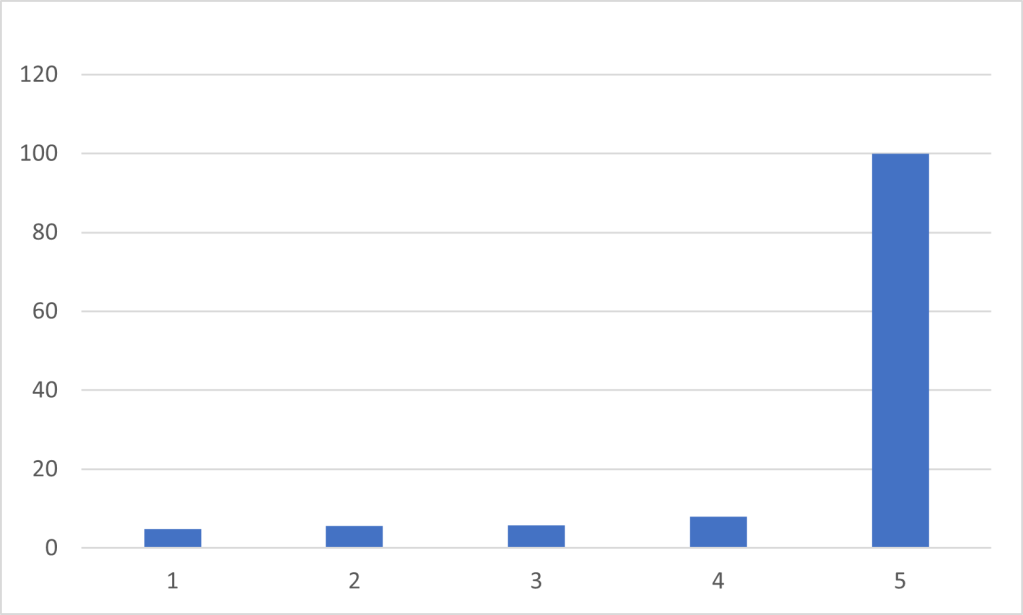

The following chart shows the total contribution of energy from non-FF or TB, with columns 1-4 representing the period 1990-2020, and column 5 is what is ‘expected’ to happen by 2050.

We can see how little decarbonization progress we have made over the last 30 years, and the extraordinary progress we expect to make over the next 26 years, towards achieving our climate goals.

Now let’s consider fossil energy used as feedstock for products, and high heat applications.

There are around 1,100 million tonnes of coking coal mined, 700 million tonnes of oil products, plus vast quantities of gas (I couldn’t find the quantity of gas used as feedstock for products or high heat applications) to make 430 million tonnes of plastics, 240 million tonnes of ammonia (fertilizer), 160 million tonnes of asphalt, plus huge amounts of high end heat for cement and steel production, and hundreds of other products and high heat applications.

OWiD does not provide data on energy used for product feedstocks, or high heat, or normal heating, or transportation, or agriculture, or mining. It’s a huge weakness in all energy calculations.

Product feedstocks, by themselves, are a huge gap in our plan for an electricity only future. A world based on renewables would have to make these products from captured carbon, because there is no unused biomass, and we cannot increase our use of biomass without causing significant further damage to the natural world that sustains us. Only if we were willing to decimate remaining forests could we replace fossil fuel products with biomass, especially as world food demand is expected to go up by 60-70% by 2050 according to the FAO.

The only example of using renewable energy to create synthetic fuel, which is the base for all fossil fuel products, is the Haru Oni plant in Southern Chile. It has a 3.4Mw Siemens Gamesa wind turbine with an expected 70% capacity factor producing an expected 20,848Mwh of electricity per year. The first ‘commercial’ (sic) shipment of e-fuels was just sent 11 months after beginning operation, and 8 months after declaring commercial operations, of 24,600 litres. That is a process efficiency of only 1.77%, assuming an annual production of 36,900 litres, without considering the energy expended in the capital ($US75M), or operating and maintenance costs (unknown or not released).

Assuming we had to make ‘products’ from this process, replacing the Coking Coal 1.1Bt = roughly 7,700Twh, plus approximately 10% of a barrel of oil (using all liquids), another 6,205Twh, the raw energy needed from renewables to do this at a 1.77% efficiency rate would be 785,000Twh, or nearly 5 times current annual energy production from all sources!!

This is before adding the energy needed to mine, process, manufacture, and transport the materials required to build it all!!

It’s a ridiculous idea.

Considering I didn’t include the products from natural gas, or any capital, operating, or maintenance costs, and even assuming significant improvements in efficiency, it’s not even close to being possible.

One final calculation to further expose the mirage.

To make the products from renewable energy, with a Haru Oni type efficiency, would require over 1.8B tonnes of copper for the energy production side of the operation, based on 5 tonnes per Mwh of a solar power plant, and over 5 hrs/day of sunshine. This would consume 100% of our current copper production for about 80 years.

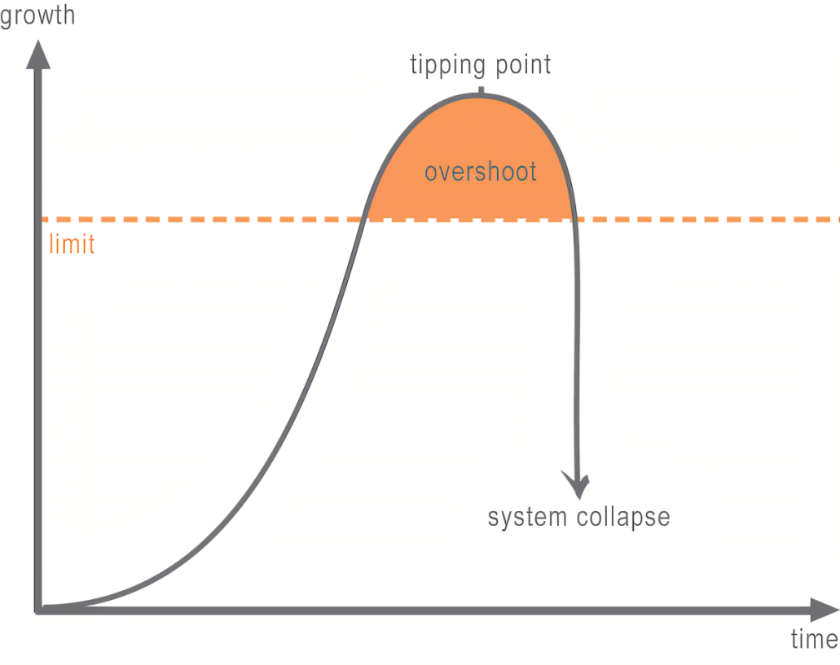

Modern civilization is a complex system. It has systems within systems, and a complexity far too high for anyone to understand as a whole. Our discussions and plans for continuing modern civilization after changing from fossil to renewable energy usually concentrate on one minor part of the overall system. It’s the only way to get an answer that looks plausible.

When multiple feedback loops are considered, it becomes obvious that we do not have the energy nor materials to keep modern civilization going for all. Unless of course, the real plan is to retain modern civilization for only a very small portion of humanity, much smaller than present…

February 15, 2024

Rob here, there are many interesting comments by Hideaway below that expand on his energy and materials analysis.

I found one comment particularly interesting because it introduced Hideaway’s background and the life path that led him to his current clear-eyed view of our overshoot predicament.

I’ve copied that comment here for better visibility.

I first learnt about limits to growth in 1975 in my first year of an Environmental Studies course. I’ve been studying and researching everything about energy and resources for decades. My wife and I moved to the country 40 years ago onto a block of land and started farming.

I was the state secretary of an organic farming group and on the certifying committee over 30 years ago. Virtually all organic, biodynamic, permaculture, regenerative properties I came across had similar characteristics. The profitable ones used lots of off property resources, which I argued was unsustainable, because of diesel use etc. I left the organic movement, also decades ago, because there was nothing really sustainable about it.

I was a believer in a renewable future for decades, always believing it was only a matter of time until they became better and cheaper than fossil fuels, which were clearly depleting. I had an accident 15 years ago, and since then have had way more time to do research than just about anyone. I really got stuck into working out how mines could go ‘green’ until I just couldn’t make the numbers work. (BTW I also had some economics and geology in my tertiary studies, but have learnt way more on both subjects in the last 15 years).

Eventually I reluctantly did my own calculations on EROEI because I just couldn’t find anything with an unbiased approach that came close to making sense. I’ve been against nuclear for decades, mainly because of humanities failure to deal with wastes and the nuclear bombs we create, so I very reluctantly calculated the EROEI using my method and was stunned at the results.

I use to be a believer in the 100:1 EROEI that everyone in favor of nuclear constantly states (before I worked it out for myself). The reality is nothing like that, it’s pitiful worse than solar and wind, which instantly made me realise that modern civilization is not sustainable any any way, shape or form.

I also kept checking the numbers I calculated for Saudi oil and a small gas project in WA. Sure enough these came to the rough numbers we need for modernity, but of course fossil fuels are leaving us due to depletion, they are a dead end anyway, even before we consider climate issues.

All my work, over years, has given me a point of reference for when the world as we know it is in real trouble. It’s when the oil extraction decline accelerates to the downside. Everything runs on oil, especially farming and mining and heavy transport. The world falls to pieces without any of these, once they struggle to get the diesel/bunker fuel they need, collapse is baked in. A date of when? no idea, but suspect we will know by higher oil prices and a failure to respond with greater oil production, then the next year a further decline in oil production, while oil prices remain high etc.

Not even coal can save modernity, the EROEI is too low. Even if we went on a massive Coal to Liquids campaign, the energy return for the cost is way too low. When coal was last king we had approximately a 70% rural population even in the west, now we have multiples of the overall population, mostly in cities, and badly degraded agricultural land.