Here is a very nice history on peak oil and a review of a new biography on its first researcher, M. King Hubbert.

Living in highly technological civilizations that generally place the greatest importance and value upon the material gadgetry and inventiveness of our societies, it should come as little surprise that the luminaries and household names that we can readily conjure and associate with are those related to the technological aspects of our lives. For example, when one mentions the telephone, the light bulb, the automobile, the airplane, or nuclear bombs, it’s likely that many a grade-schooler can rhyme off the names Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, the Wright brothers, and, perhaps, Albert Einstein.

But segue into more ecological matters and the fathers and mothers of these vocations are certainly not household names the way the aforementioned are. For what comes to mind when we think of organic farming, climate change, the environmental movement, or limits to growth? For most of those who flick light switches on and off as much as they eat food and depend on stable planetary ecological balances, the answers are probably little more than a shrug. While children can quite easily conjure up the aforementioned names, you’d be hard pressed to find even an adult who could easily slip off of their tongues the names Sir Albert Howard, Svante Arrhenius, Rachel Carson, and the team of Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, and Jørgen Randers.

But while the topics of organic farming, climate change, and the environmental movement can certainly elicit recognition in the average citizen, the reality of peak oil quite often does not, with even less of a recognition expected in reference to the person that initially brought it to our attention. That largely unknown individual would be M. King Hubbert, the subject of Mason Inman’s timely new biography, The Oracle of Oil: A Maverick Geologist’s Quest for a Sustainable Future.

As Inman describes it, after having spent his early formative years on a farm in the Hill Country of Central Texas, and gone through two years of community college, a young Hubbert ended up making his way through various hardscrabble jobs on his way to the University of Chicago. It was there that the mathematically inclined Hubbert got exposed to a variety of disciplines that would aid him in his future endeavours, those ranging from geology to physics to math.

It was while still an undergrad that the first inklings of Hubbert’s future interest can be seen, that moment when he first glimpsed a chart depicting the exponential growth of coal extraction rates. After a following lecture on petroleum extraction, Hubbert apparently couldn’t help but muse to himself, “How long will it last?” For now, as he put it, it was “Difficult to estimate reserves.”

By no means though was Hubbert afflicted with a one-track kind of mind, for as Inman astutely weaves within his story, Hubbert, and at only 26-years-of-age, accepted a job offer to teach geophysics at Columbia University in New York City, the place where he became an original member of what would become the second focus of his life – the nascent movement soon to be known as Technocracy. In short, Technocracy was a not-quite totalitarian system whereby government-owned industries were envisioned as being managed by scientists, engineers and technicians. In fact, all of North America, even all the way down to Venezuela (because it had oil?) would be under the “continental control” of a united government, known as a “Technate.” Technocracy also disdained “the price system” in favour of “energy certificates,” a highly relevant notion that Inman fortunately repeatedly returns to.

In the meantime, Hubbert was all the while dissatisfied with the supposedly common sense notion that the extraction of a given mineral increases exponentially until one day, poof!, there’s nothing left. As he understood it, extraction and depletion rates could be related to the so-called S-curve that can be seen in an isolated pair of breeding fruit flies: their population soars and eventually tapers off at a plateau (or a flattened peak). And as Hubbert was in the minority with his belief that there were limits to growth, he similarly saw various facets of industrial society as fitting on this S-curve.

Being one of the leading proponents of Technocracy and an ardent writer on its workings, it was in Technocracy publications that Hubbert dabbled in writing about peaks and declines of resources. Come 1938, Hubbert came up with his first, but somewhat unsubstantiated (and rather off), estimate of the year that US oil extraction rates would peak: 1950. But having moved from academia to the government in the early 40s, it wasn’t until he then took a job at the US branch of Royal Dutch Shell in 1943 (eventually becoming the top geologist in a new lab it created) that Hubbert would have the resources and access to information that would allow him to formulate a more detailed analysis which led to his ground-breaking predictions.

For it was on March 8th, 1956, that Hubbert gave his talk “Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels,” his revelatory paper that laid out his thoroughly analysed prediction that US oil extraction rates would peak sometime between 1965 and 1970 (to go along with a global peak in 2000). I won’t spoil things with a recitation of the rather humorous tensions, but I will point out that Hubbert was in fact correct, and that US oil extraction rates peaked in 1970. Furthermore, while much derision of Hubbert’s findings resulted both before and after 1970 (to go along with a smattering of praise), what may come as surprising to those thoroughly familiar with peak oil but too young to have been around back then (such as I, who was busy being born while President Jimmy Carter was wearing cardigans and having solar panels placed on the White House) is the amount of media attention given to estimates of US oil supplies, including both before and after Hubbert’s famous paper.

For while peak oil is nowadays generally dismissed – and more commonly ignored – by the mainstream media in lieu of financial abracadabra and/or dreams of a 100% replacement of fossil fuel energy with renewable (“renewable”) energy, the amount of serious talk that domestic US oil supplies garnered in the mid to late-mid 20th century is comparatively astounding. Inman’s surprising historical account relays the fact that the topic made the front pages of the New York Times and the Washington Post on more than one occasion, while the New York Times even visited Hubbert at his home to interview him! And even more absurd is Inman’s account of the US administration’s – all the way up to President Jimmy Carter’s – interest in Hubbert’s work, President Carter even making a quasi-reference to Hubbert’s work in one of his talks.

The question(s) that these shocking revelations (shocking to me at least) that Inman conveys is, What happened? Why were oil supplies and extraction rates such a big issue a few decades ago, when today the talk, if anything, is all about energy prices?

As Inman points out, one of the ordeals that began to drown out talk of oil extraction rates was the Watergate scandal of 1973. Following that, the “doom and gloom” of President Jimmy Carter (Carter’s sources called for worldwide oil extraction rates to peak in the mid-1980s [!?], while Hubbert’s calculations saw 2000 as the peak year) was no match for the sunny optimism of Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election, resulting in a new President and the removal of the White House’s interloping solar panels.

Jump ahead a few decades, and from what I can tell, not only does it seem that this Reagan-esque sunny optimism continues to reign supreme, but that it has imbued itself into the thinking of many progressives and environmentalists today, through the optimistic attitude of the “clean and green” notion that “renewables” can provide a 100% substitution for fossil fuels. As far as I can see it, it is this techno-optimist attitude of technology-as-saviour, to go along with another round of obeisance to financialization as itinerant saviour, that has convinced many people that energy supplies, and thus peak oil, need not be an issue (anymore, supposing that they ever really were).

But as Inman’s account also explains, Hubbert wasn’t quite averse to the techno-optimist way of thinking either. Although he did eventually do away with his staunch support for nuclear power, Hubbert ended up trading a reliance on nuclear power for a rather oversized belief in solar power. That is, Hubbert envisioned deserts covered in solar panels that would generate electricity of which could be converted into methanol or to generate hydrogen, and that such ventures could power high-energy societies (New York City!) for thousands of years. It was thus Hubbert’s belief that

“with our technology and with adequate supplies of energy, we ought to have a lot of leisure. And the proper use of this leisure can bring us an intellectual renaissance.”

This attitude gels with the stated Technocratic “embrace [of] the abundance created by machines,” which for me is hard to equate with the notion that peak oil and diminishing energy supplies in general imply less energy to power those machines, unless you believe in the sunny optimism of solar-panel-covered-deserts (to go along with other “renewables”) that can match the energetic output of fossil fuels (which the low EROEI levels of, say, solar panels, says isn’t quite feasible).

Having said all that, Hubbert did fortunately have the all-too-rare understanding that

“One of the most ubiquitous expressions in the language right now is growth – how to maintain our growth. If we could maintain it, it would destroy us.”

So although, and from my understandings, Hubbert had the questionable belief that nuclear power, and then solar panels, could provide not quite infinite growth but (rather conveniently?) a kind of infinite steady state of what the current energetic usage happened to be at the time, he did nonetheless realize that none of this could do anything for the problems of overpopulation and diminishing water supplies.

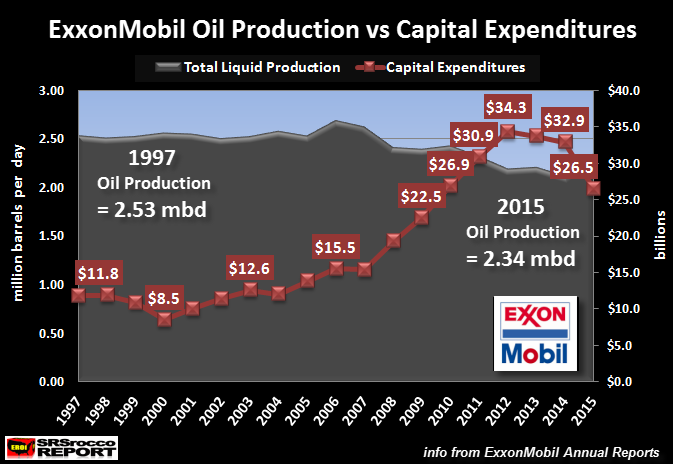

Bringing things into the present, Inman conveys the fact that worldwide conventional oil extraction rates peaked (or perhaps hit their plateau) in 2006 at 70 million barrels per year, finally dropping down to 69 million barrels per year in 2014. As it is, the only thing keeping overall oil extraction rates increasing – and giving the last push to the economic growth which Hubbert so despised – are the unconventional oil supplies of tight oil (via fracking) and tar sands oil.

This brings us back to Technocracy’s disdain for “the price system” (or as Hubbert put it, “the monetary culture”), which was the status quo and scarcity-based economics system that measures everything in dollars and cents, and which ignores physical limits. For as Technocracy conversely saw it, money would be abandoned for “energy certificates,” allowing for everything to be paid in their energy equivalent.

Upon first coming across the name M. King Hubbert some ten years ago I happened to read about Hubbert’s disagreement with our practice of fractional-reserve banking, of which I’ve never seen mentioned again until Inman’s book (kind of, as Inman doesn’t mention fractional-reserve banking directly). It is from this knowledge that I’ve come to understand the situation of diminishing energy supplies: since money is a proxy for energy, limits on energy supplies will imply limits to the continuance of our economic (Ponzi scheme) system, leading to an inability for sufficient payments to service even the interest payments on previous loans – which implies and will contribute to the collapse (implosion) of economies, be it slowly or quickly. As Hubbert put it, “exponential growth is about over. We’re entering something new.”

But not being much of a fan of a grandiose Technate myself (nor of the belief that there would ultimately be enough alternative energy supplies to maintain such a massive and centralized system anyway), we could still work off of Hubbert’s disdain for “the monetary culture” towards something like the Ecological Economics of Herman Daly and Joshua Farley, a discipline which is also in favour of moving away from fractional-reserve banking and the notion of infinite growth. And since peak oil means growth is coming to an end, perhaps a look to biophysical economics (see Energy and the Wealth of Nations by Charles Hall and Kent Klitgaard, or the new journal BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, edited by Hall, Ugo Bardi, and Gaël Giraud) could help us to envision a worthy alternative to Technocracy’s monetary substitution.

Regardless, there does seem to be merit for Hubbert’s belief in perhaps a partially planned economy, supposing that that would even be politically possible. Market forces are quite obviously doing little to nothing to ween us away from the usage of fossil fuels (be they diminishing or not), and the primary effect that high oil prices (reaching $147 a few years back) had was to spur investment in the higher costing unconventionals.

In the meantime, supposing that conventional and unconventional oil supplies continue their slight overall increase for years to come, this also poses a problem in light of carbon dioxide levels contributing to climate change. Inman thus poses the ultimately unavoidable and extremely pertinent questions: Do we really think market forces will come to our rescue? And if not, are we going to impose limits on ourselves, or are we simply going to sit back and wait until nature imposes those limits for us?

So whether you’re new to the notion of peaking oil supplies or rather familiar with it, I can certainly say that The Oracle of Oil has much new to shine on the story – and now history – of peak oil. With oil supplies being what they currently are, and with no off-planet supply to make up for what will this time not just be a US shortfall but a planetary shortfall, Inman’s book could certainly do us a favour by helping us to familiarize ourselves with the reality of peak oil, and by helping us to make M. King Hubbert the household name it ought to be.

That is of course a lot to ask, and after the virtual silence on peak oil that occurred after the global peak of conventional oil extraction rates in 2006 (to go along with all that has ensued since), one couldn’t be blamed for expecting little different upon the reaching of the global peak of conventional and unconventional oil extraction rates in the coming months or years (?). But one can always hope of course.

Godspeed the overall global peak?