I want to discuss the pros and cons of broad public awareness of our overshoot predicament.

Disadvantages of Overshoot Awareness

Sooner Economic Contraction

Today’s global economy is a massive bubble waiting to pop.

Bubbles are created when many people believe that the price of an asset will go up and use debt to purchase the asset. This creates a self-fulfilling positive feedback loop as purchases bid up the price which increases collateral for more debt to fund more purchases.

Assets inflated by a bubble do not generate sufficient wealth to justify their price. Bubbles are accidents waiting to happen because an unpredictable shift in belief towards realism or pessimism will cause a collapse in price as the market unwinds its debt leverage, usually oscillating below fair value and damaging innocent bystanders in the process.

Bubbles have been common throughout history but today’s bubble differs in that instead of one asset class such as dot-com or tulip mania, all asset classes are inflated and its size relative to GDP, and especially future GDP, is unprecedented.

A few examples:

1) The quantity of government debt and other obligations exceeds the servicing ability of future taxpayers, doubly so when interest rates rise in response to the risk of default. Government economic models assume more growth than is physically possible with depleting fossil energy. This means all currencies are over-valued. Currencies have retained their value because most people still believe what their governments tell them.

2) The quantity of corporate and private debt exceeds the servicing ability of realistic future income. This bubble has not yet popped because governments have held interest rates at near zero for 8 years. When interest rates start to rise, as they must when default risks become impossible to deny, this house of cards will collapse in defaults.

3) Stock prices have been inflated by cheap debt and the majority’s belief in infinite growth. Companies have used debt to buy back stocks to falsely improve their appearance to investors. Speculators have used debt to profit from stocks. Central banks have used debt to manipulate stock prices up to create the facade of economic well-being. A rational analysis of stock prices relative to future earnings, especially in light of declining net energy, and an eventual increase in interest rates, would show that stocks are a massive bubble waiting to pop.

4) Real estate is over priced. In the long run the average price of a home must equal the average income’s ability to obtain and service a mortgage. Incomes are falling and will continue to fall as energy depletes. When interest rates rise, many mortgages will become unaffordable and real estate prices will drop. Furthermore, the availability of mortgages, which are needed to support real estate prices, is dependent on a financial system that can create generous credit, which in turn is dependent on reasonable economic growth, which is not possible with declining energy.

Central banks have done a surprisingly good job over the last 8 years of not permitting the bubbles to collapse. Their ability to continue supporting the bubbles is highly dependent on public sentiment. If the majority loses faith in the central bank’s ability to stimulate growth then it is game over and the economy will experience a large correction.

A disadvantage of overshoot awareness is that it would trigger an economic correction sooner than letting the random vagaries of belief take their course, or letting mathematics and physics force the correction.

The larger a bubble gets the more pain it causes when popped because its deflation usually swings below the mean on the way to reality, and more innocent bystanders get hurt.

It’s best to avoid a bubble in the first place, and although we’re well past that point, the sooner we remove the bandage the better off we’ll be in the long run.

Put more succinctly, there is no free lunch.

Hoarding and Shortages

We live in a very efficient world. Companies use just-in-time delivery to minimize inventory and waste. Citizens no longer have root cellars or put up preserves for winter consumption because grocery stores are so abundant and convenient. Grocery stores have about 3 days stock on hand and depend on a complex network of credit, energy, and technology to operate.

Resilience to shocks is improved by building buffers and redundancies. A probable outcome of broad overshoot awareness would be buffer building induced shortages of important staple goods.

This risk could be mitigated by rationing policies as were used during World War II.

Mental Health Problems

Acknowledging overshoot forces one to question and overturn several hundred years of growth based culture, religion, education, and deeply held beliefs by the majority. The adjustment can be traumatic.

To succeed in today’s society you must contribute to overshoot. An aware person knows they can be happy with less consumption, but choosing a frugal lifestyle often makes you a failure in the eyes of an unaware majority.

There is no “happy” solution to overshoot. The future will be painful for most. The best possible outcome is a lot of hard work to make the future less bad. It is difficult to be motivated with this awareness.

For these reasons a common outcome of overshoot awareness is depression.

Mental health problems perhaps could be minimized if overshoot awareness was accompanied by an understanding that overshoot is a natural outcome of abundant non-renewable energy and evolved human behavior. Perhaps not. A renewed belief in religion is a more likely outcome.

Having the majority and their leaders aware and working together to prepare for a low energy world, rather than individuals working in isolation, offers the best chance of minimizing mental health problems. But this outcome would require the majority to override their inherited denial of reality which makes it improbable.

Relationship Damage

Becoming aware of overshoot before friends and family become aware can damage relationships. The aware person wants to educate and warn those closest to them. Those not aware usually do not want to hear the message because most humans have an evolved tendency to deny reality. This stress can damage families and friendships.

Advantages of Overshoot Awareness

Fewer Despots and Wars

As energy depletes and the climate worsens, incomes, wealth, and abundance will decline. Eventually there will be life threatening shortages of food and other necessities.

Tribes evolved to survive in times of scarcity by fighting other tribes for resources. The most united tribes with the most warriors willing to sacrifice their lives often had the best chance of winning and surviving. This in part explains the evolutionary success of religions.

To fight effectively requires a well-defined enemy. There is thus a natural tendency to blame other groups for hardship.

In the absence of understanding what caused scarcity, the majority will support despots that blame others, and these despots will start wars.

Wars in the past often improved the lives of the winners because the most important resource was land.

Wars in the future will make things worse for both the winners and the losers because the most important resource is energy. Modern wars consume large amounts of energy and will accelerate the depletion of the resource that is being fought over, leaving less energy for everyone when the war ends. This is sometimes referred to as a resource depletion death spiral.

It is of course possible that a despot will decide to eliminate the energy-consuming population of its enemy with nuclear weapons. This scenario will also make everything worse for both the winners and the losers, for obvious reasons.

Humans would therefore be wise to avoid future wars. Awareness that overshoot is causing scarcity, that no one is to blame, and that war will make things worse, is the only reasonable path to avoiding future despots and wars.

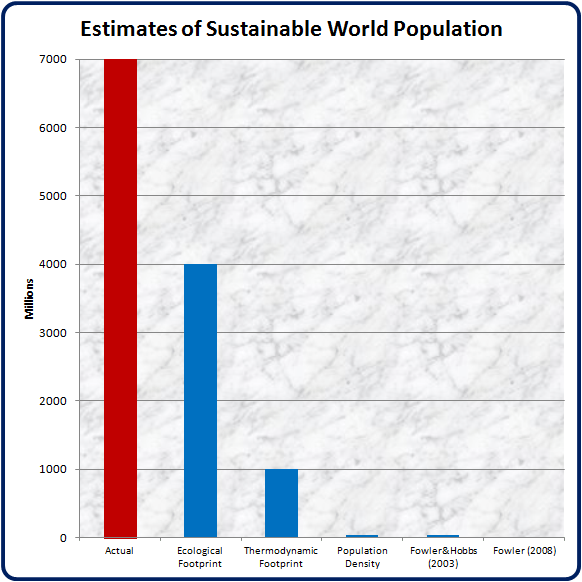

It would be much wiser to use the remaining surplus energy to proactively reduce our population, and to create infrastructure required to survive in a low energy world.

But again, as mentioned above, we first need to break through our evolved denial of reality.

More Acceptance and Cooperation

Awareness of the underlying overshoot related causes of problems experienced by individuals would increase the acceptance and cooperation necessary to make a bad situation better.

Most viable mitigation strategies will require broad societal cooperation. These strategies include rationing of scarce resources, proactively shifting economic activity from one sector to another, progressive taxation and wealth redistribution, and generally more government involvement in all aspects of life.

More Preparedness

Although per capita energy is in decline, we still have a considerable amount of surplus energy available to do useful work. The longer we wait the less surplus energy will be available to help us prepare for a low energy world.

Broad awareness of overshoot would accelerate our preparedness for the inevitable, and reduce future pain.

Positive Behavior Changes

Although there is no “happy” solution to overshoot, a broad awareness and voluntary shift in behavior would help. For example, a lower birthrate, reduced luxury consumption, less travel, and more care of the commons would all help.

Avoiding a Chaotic and Dangerous Crash

All of the above advantages to overshoot awareness fall under the umbrella of replacing a chaotic and dangerous crash with a more orderly and planned contraction.

Many of the things that made life pleasant over the last century will be at risk in a chaotic crash. These include democracy, law and order, health care, social safety nets, peaceful trade, environmental protection, and functioning electricity, water, sewer, and communication grids.

We would be wise to preemptively release the pressures that threaten a chaotic crash.

Conclusions

On balance I think the advantages of overshoot awareness outweigh the disadvantages.

A society with its majority understanding overshoot, what caused it, and that no one is to blame, would help make the future less bad.

Unfortunately our evolved denial of reality is a powerful impediment to awareness.

I fear the majority will never understand what is going on.

I wrote more on this issue here.